Edward Mitchell Bannister was born on November 2, 1828, in the small seaport town of St. Andrews in New Brunswick, Canada. It was known to the Passamaquoddy First Peoples as Qua-nos-cumcook. Edward’s father, also named Edward Bannister, was from Barbados, and died when the younger Edward Bannister, was either 4 or 6 years old. The tragedy created both an emotional and financial hardship on the family, and forced young Bannister’ s mother, Hannah Alexander Bannister, a woman of Scottish descent, but born in St. Andrews, to raise young Edward and his older brother, William, by herself.

Because Bannister was born in Canada, like Robert S. Duncanson (who we covered previously), he didn’t experience the same oppression and deprivation that many African-American children had to endure. He attended a village grammar school and received a far better education. This is according to William Wells Brown, who, before Bannister was nationally recognized, wrote his first biography in 1863.

Hannah Bannister, William and Edward’s mother, not only pushed Edward in his school studies, but she also nurtured his natural artistic abilities. So, while still a boy, he gained a bit of a local reputation for his crayon portraits he’d created. However, sometime, in his teens, Edward and William’s mother passed away. Poor thing. And after her passing, William moved to Boston in the United States, because he wasn’t in a position to care for his younger brother, Ned. That’s what Edward was known as by the people close to him.

This must’ve been incredibly stressful for both boys, but especially for poor young Ned. Fortunately, though, he was taken in by a wealthy attorney named, Harris Hatch. Bannister lived in an attic bedroom on the family farm and was assigned specific chores. With this arrangement, Bannister also gained access to the attorney’s well-shelved library where he found inspiration in two family portraits.

I wasn’t able to track down who these two people were, but… Oh, Bannister loved these portraits. He reproduced them every chance he got – and everywhere he could. He drew them on barn doors, he drew them on fences – any flat surface that wouldn’t get him into trouble. He drew them.

It’s not clear when Bannister left the Hatch home, but it’s speculated that he left in his late teens. At first, he became a cook, but later became a sailor, visiting Boston and New York often.

During these visits, he explored libraries, museums, and galleries, which greatly expanded his appreciation for art. Of course, he gravitated to these places. He loved art. He had natural raw talent. And these places just fed his desire to learn to master the craft, but, he couldn’t find a mentor. So, to stay in Boston and pursue his passion for art, Bannister became a barber in 1853– and later, a hairdresser.

It was here, in the salon, where he would meet his future wife, Madame Christiana Carteaux. She was a successful African-American businesswoman and owner of the salon where Bannister worked. Born in North Kingston near Providence in 1822, Carteaux was sought after my many socialites in the area because of her elegance and intuitive understanding of their needs. Carteaux and Bannister struck up a close friendship and were married by 1857.

After dabbling in styling women’s hair in the latest trends and tinting portraits, a side gig he’d taken on after arriving in Boston, he eventually shared studio space with portrait artist, Edwin Lord Weeks, who later became known for his works featuring subjects from India.

I did get a chance look at some of Edwin Lord Weeks works. Out of curiosity. I found out that he was classified as an Orientalist. I actually didn’t know that was a thing. But his work is beautiful. I love what he did with light. H is background included wealthy tea merchant parents who traveled a lot. So, Weeks’ paintings, I think, are more interesting because he created images, most American would have never see in person. Snapshots of life from a far different culture and now, time period.

(Act II)

Bannister’s paintings, in contrast, primarily drew inspiration from biblical stories and themes, and were featured in group exhibitions at the Boston Art Club and Museum. In addition to biblical scenes, he painted portraits, local landscapes, and scenes from history.

Most of his works from this time period have been lost. One such piece, painted before 1855, is titled “The Ship Outward Bound” and belonged to Dr. John B. Degrassi, the first Black physician in Boston and a close friend of his. Bannister also created portraits of Degrassi in 1854 and his wife in 1852. In 1857, he completed a landscape titled “Dorset, New Hampshire.”

Fortunately, at the time, Boston had a strong abolitionist presence, which greatly benefited Bannister. This support allowed him access to educational institutions like the Lowell Institute. The Lowell Institute was established in 1836, with a mission to provide knowledge to people in the area, regardless of gender, race, or economic status. They actually still exist today, and have achieved all this by organizing free public lectures and educational programs.

Bannister also had opportunities to exhibit his work in prominent art associations. And like I mentioned, during the 1850s, Boston’s commitment to abolitionism grew, with many supporters and financial backers of John Brown living there. For those who may have forgotten, John Brown was a White abolitionist who organized and led a raid and was later hanged in 1859, for that raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in an attempt to end slavery.

One of the Black abolitionists focused on showcasing that Black individuals could excel in the arts was William Wells Brown. When I’m referring to him, I’m just going to address him by his full name so that you don’t confuse him with John Brown. William Wells Brown had escaped from slavery and moved to Boston when he was 19-years-old. He adopted the name, “Wells Brown” from the Quaker couple who took him in after his escape.

In his book titled “The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements,” published in 1863 by James Redpath (the first biographer of John Brown), William Wells Brown also included an account of Bannister’s life and accomplishments.

The book featured profiles of about 50 Black men and women, including Nat Turner, the leader of a slave uprising in Virginia; writer Alexander Dumas; mathematician Benjamin Banneker; educator Charlotte Forten; and Captain Andre Callious, who led Black troops in an attack on Confederate forces at Port Hudson in New Orleans. The book also highlighted two Black artists, Edward Bannister and sculptor, Edmonia Lewis. The overview of Black history in this book surprised and captivated a lot of people.

Including me! So, I was thinking about reading this book on the podcast later, maybe to add some interesting content while I create the next episode – especially since I sometimes have big gaps in between each episode…We’ll see…

William Wells Brown offered a detailed description of Bannister, who had his studio in Boston’s Studio Building at the time. By the way, the Studio Building was built in 1861, and used to be a prominent building on Tremont Street that had a lot of artist studios, theater companies and other businesses. It burned down in a fire in 1906.

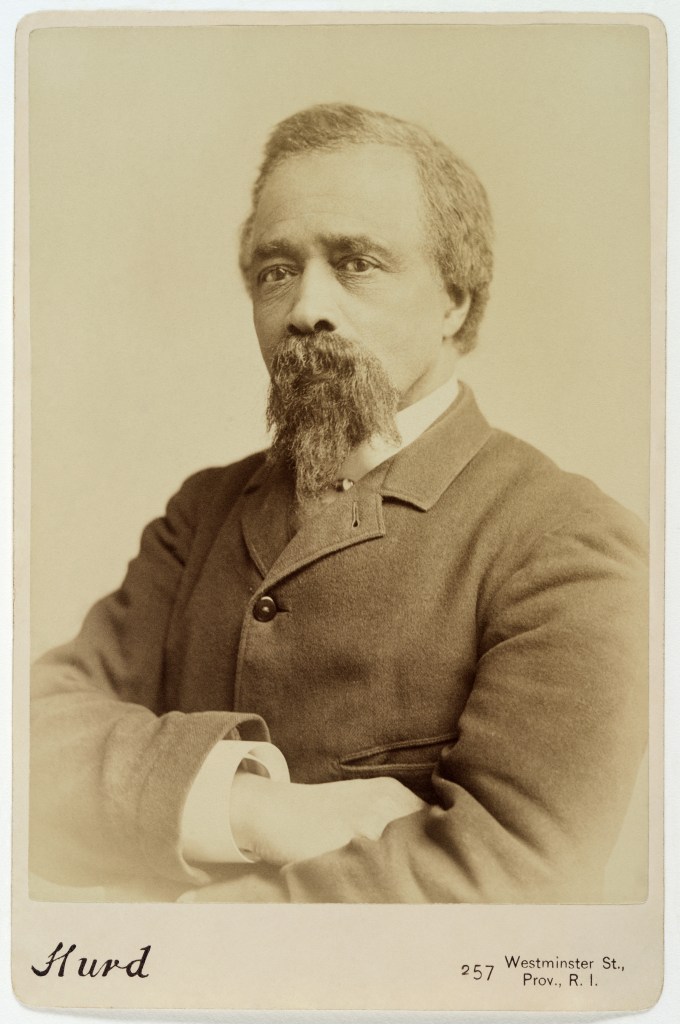

William Wells Brown described Bannister as “spare-made, slim, with an interesting cast of countenance, quick in his walk, and easy in his manners.” Also, William Wells Brown provided insights into several of Bannister’s artworks. One of these was a landscape painting, another depicted a genre scene titled “Wall Street at Home,” featuring “an elderly gentleman seated in his comfortable chair, boots off, and slippers on, avidly reading the latest news.” Brown also discussed another of Bannister’s works, a historical piece titled “Cleopatra Waiting to Receive Marc Anthony.”

At the time the book was published, Bannister was 35 years old. The book’s inclusion of him alongside outstanding Black men and women brought him to the attention of numerous individuals, particularly in Boston, who might not otherwise know him.

In that same year the book was published, President Abraham Lincoln responded to Frederick Douglass and other African-American leaders’ demands, granting Black men the opportunity to fight as soldiers against slavery. Both Bannister and his wife were active in the fight for equal pay for Black soldiers serving in the Union army. In Massachusetts, Governor John Andrews was authorized to organize Black regiments, and Black men eagerly joined, only to find out that Union Army leaders were offering them $10 a month with a $3 deduction for clothing, whereas white soldiers received $13 a month plus an additional $3.50 for clothing. This unequal pay scale was justified by labeling Black soldiers as laborers rather than fighters.

So, just a quick summary here: White soldiers got more money and a uniform stipend, while Black soldiers got less money plus were docked pay to cover uniform costs.

When they discovered this disparity, the Bannisters immediately took action to raise funds to bridge the gap. With Governor Andrews’ approval and his summoning of the state legislature to address the issue, Bannister’s wife organized a substantial effort to sell valuable items obtained from prominent Bostonians, including many of her clients. Bannister oversaw the decoration of the hall and the arrangement of tables and items, which were either sold directly or auctioned. This initiative swiftly generated about $4,000 and drew attention to the issue of unfair pay, ultimately prompting Congress to act on equalizing the pay.

The Bannisters relocated to Providence, Rhode Island, in 1870. Edward already had friendly connections with Providence artists from his time in Boston studios and galleries. One of these artists was Connecticut born portraitist, John Nelson Arnold, Bannister’s friend since their days at the Lowell Institute. But Edward wasn’t the only connected one. His wife, Christiana, also had strong ties in Providence, including relatives and prominent socialites who got their hair done in her salon.

The move to Providence allowed Bannister easy access to the rural and wooded landscapes crucial for Barbizon painting. For the most part, The Barbizon School was Bannisters signature style. Originally, its pioneers of the Naturalist landscape painting movement, gathered in the town of Barbizon near the Forest of Fontainebleau outside Paris. The artists were diverse in their backgrounds and styles, and they shared a passion for painting outdoors, elevating landscapes as independent subjects. The forest’s rugged beauty inspired artists like Corot, Rousseau, Millet, Renoir, and Manet. In contrast to Neoclassicism’s idealized depictions (like those of the Hudson River School), these artists approached painting naturally, truthfully representing what they observed in the countryside’s colors and forms.

Bannister set up his studio in the Woods Building, where his friend, John Nelson Arnold and other artists had their studios. As he focused more on landscapes and scenes of the Narragansett shore, Bannister gradually reduced the amount of religious and historical works he produced.

(Act III)

About four years after moving to Providence, Bannister went on a sketching trip to William Goddard’s farm near Potowomut. I believe this land is now a state park. It was during this visit, Bannister was drawn to a cluster of oak trees and created the painting, “Under The Oaks.” Both he and fellow artists who visited his studio considered this to be his finest and most exceptional work.

In Providence, the artistic community was well aware of the upcoming 1876 United States Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, which promised to showcase the most extensive collection of art ever seen in the nation. This event marked a time when American museums were just beginning to emerge. Alongside renowned European artworks, the exposition would feature pieces from America’s early masters like Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley, as well as contemporary American artists.

Bannister submitted “Under The Oaks” to a regional jury in Boston, and it was chosen as their top entry. The Boston Traveler’s art critic hailed it as “the greatest of its kind by an American artist.”

At the Centennial Exhibition, Bannister’s painting competed with notable works by Albert Bierstadt, J.F. Cropsey, and Frederick E. Church. Identified as “Number 54 – Under The Oaks – E. M. Bannister,” it earned the bronze medal, the most prestigious prize for oil painting at the event. This medal was recognized as the highest painting award, as reported in the Providence Journal on January 11th, 1901.

In his recollections, George W. Whitaker, another Barbizon School artist and close friend of Bannister for three decades, recounted Bannister’s personal experience at the Centennial. When he saw his painting in the catalog, Bannister was so excited. His childhood dream was coming true! Then he located his work, which was displayed prominently, and this made him so proud. Later, Bannister said:

I learned from the newspaper that “54” had received a first prize medal, so I hurried to the committee rooms to make sure the report was true. There was a great crowd there ahead of me. As I jostled among them, many resented my presence, some actually commenting within my hearing and in most petulant manner: what is that colored person in here for? Finally, when I succeeded in reaching the desk where inquiries were made, I endeavored to gain the attention of the official in charge. He was very insolent. Without raising his eyes, he demanded in the most exasperating tone of voice, “Well what do you want here anyway? Speak lively.”

” I want to inquire concerning number 54. It is a prize winner?”

” What’s that you?” said he.

In an instant my blood was up; the looks that pass between him and others in the room were unmistakable. I was not an artist to them, simply an inquisitive colored man. Controlling myself, I said deliberately “I am interested in the report that Under The Oaks has received a prize. I painted the picture.”

An explosion could not have made a more marked impression. Without hesitation he apologized to me, and soon everyone in the room was bowing and scraping to me.

Bannister’s African-American heritage was openly acknowledged, and his achievements were recognized by his community. Two African-American reporters reviewed his award-winning painting in the Christian Recorder of the American Methodist Episcopal Church. FYI, the Christian Recorder is still in publication. On its website, it says it’s the oldest existing African American newspaper in the United States.

One review, authored by Robert Douglass Jr., a skilled Philadelphia artist known for portraiture and miniatures, praised “Under The Oaks” as a serene pastoral scene featuring a shepherd and sheep beneath a splendid cluster of oak trees. He further noted that the painting was highly admired and expressed his delight that it had earned a medal. Douglass Jr. drew parallels between it and the masterpieces of John Constable, the renowned English landscape painter.

Following its award, “Under The Oaks” was sold through art dealers Williams and Everett to a Boston resident named Mr. Duff for $1,500, a good amount of money for a painting at the time. That would be about $54,000 today. Bannister’s share of the proceeds was $850, about $31,000 today.

In line with the typical dealer-artist relationships of that era, Bannister was at first, unaware of the painting’s buyer. It was only years later that he accidentally discovered where it was and received permission to view it. He found it proudly displayed in the front hall of Mr. Duff’s residence, beautifully hung on a French landing with an easy chair positioned for Duff to contemplate its tranquil beauty each morning before heading to his office. Regrettably, neither the painting nor the medal awarded to Bannister can be located today.

Bannister’s old friend, Whitaker proposed uniting artists, professionals, amateurs, and art collectors in a club. They initially met in Bannister’s studio, focusing on issues with dealers who charged high prices and provided little return. Exhibitions and sales opportunities were scarce.

After two years of discussion, Bannister, Whitaker, and self-taught landscape artist, Charles Walter Stetson, invited a larger group of artists to join them in February 1880. They considered establishing a gallery and sales room but opted instead for an inclusive art club, welcoming artists, amateurs, and art enthusiasts, including those in music and literature. The idea received a lot of community support.

The Providence Art Club was officially founded in, Norwegian artist, Eimerich Rein’s studio on February 19th, 1880. Bannister was the second to sign the agreement, following J. S. Lincoln, the elected president. Founding members included Eimerich Rein, John Nelson Arnold, George Whitaker, Charles Walter Stetson, Sydney Burleigh and Rosa Peckham. Bannister served on the executive committee for many years.

As a professional artist, Bannister primarily painted: serene blue-gray skies with breezy white cumulus clouds in the late afternoon, the rolling Rhode Island landscape, and the picturesque Narragansett dunes and shores. Initially, his style reflected the influence of Barbizon artist, William Morris Hunt, his revered mentor. Over time, he embraced his unique vision of nature, moving away from the Barbizon style.

His paintings consistently achieved their impact through simplicity, patience, and careful observation of nature. In contrast to the imaginative and dreamlike landscapes of artists like Robert Duncanson and Frederick Church, Bannister’s work reflects his enduring admiration for nature’s gifts while exuding a tranquil, balanced, and steadfast quality, much like his own personality.

Whitaker, who had studied Barbizon painting in France under the guidance of Millet and other masters, fondly reminisced about a trip he and Bannister took to a significant Barbizon painting exhibition in New York City:

There my friend was in his element. As we walked from picture to picture, talking more earnestly than we were aware, we noticed we were being followed by a stately old gentleman of the old school who soon introduced himself, giving his name and saying he was in officer of the Metropolitan Museum and would we, after doing this exhibit, be his guest at the museum? I am sure he had been attracted by Bannister’s talk and actions – namely, his hands, feet, body, and head, so enthusiastic did he become. We accepted and were royally entertained. It was one of the greatest treats I ever enjoyed and reminded me of a day spent with George Inness in Paris 25 years ago.

One intriguing aspect of his friend that puzzled Whitaker was that although Bannister was an experienced seaman and spent much of his time sailing, he didn’t concentrate on marine paintings. For more than 25 years, he sailed his small yachts in Narragansett Bay and Newport Harbor. Whitaker noted, “I have had the pleasure of being in his company on his boat for weeks at a time, and I fancy that here he made his mental studies of cloud… land… these were days when his cup of joy was full.”

Bannister received regional honors as well. At the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanics Association annual exhibit, a significant Boston show, he earned a bronze medal in 1878 and silver medals in 1881 and 1884. Notable art collectors, including Isaac C. Bates, Eliza Radeke, and H. A. Tillinghast, purchased his paintings, and these patrons were associated with the Rhode Island Museum of Art.

Despite the recognition, Bannister lamented his lack of formal training. In a letter to Whitaker late in life, he expressed his frustration, saying, “I cannot do all that I would like in art due to my lack of training, but with God’s help, I hope to deliver the message entrusted to me.”

Unlike the meticulous detailing seen in Hudson River School paintings, Bannister’s art focuses on massive shapes like trees, mountains, rocks, and trails. These shapes emerge through the sharp interplay of light and shadow, often emphasizing black and white values over color relationships. As Whitaker noted, “He knew the value of deep shadows as a foundation for his painting. His color palette was subdued, playing with shades of gray.”

In a work titled, “Approaching Storm,” a departure from his tranquil landscapes, you can see a man urgently seeking shelter from a vantage point atop a nearby hill. The path he travels is in the foreground, with wind-tossed trees in the middle distance. The left hills and the sky above form the background, creating a relatively narrow spatial depth. When “Approaching Storm” is turned upside down, it becomes evident that the foreground, trees, and hills blend into one large silhouette against which the man stands out.

In his landscapes, Bannister conveyed mood and emotion through his own observations, using a sketchy brushwork style. This unfinished approach had the spontaneity of John Constable and some Barbizon painters, setting it apart from the controlled finish of Hudson River School artists.

Bannister was intrigued by the unpredictable aspects of nature—how clouds, light, and trees behaved in changing weather conditions. “Approaching Storm” exemplifies his fascination with these natural phenomena. His best works found unity in their underlying feeling and atmosphere, skillfully balancing elements, rather than emulating the constructed landscapes of Claude Lorrain or later artists like Cezanne. Bannister liked to capturing nature’s imperfections. He derived his colors directly from his subjects, resulting in muted earthy tones.

In his later years, Bannister faced challenges as changing tastes made it increasingly difficult to sell his work. This posed more financial hardships for his family. Eventually, his health declined, forcing him to give up sailing, and lapses in memory made simple walks unsafe. Mentally and physically he deteriorated. On the evening of January 8th, 1901, he passed away from a heart attack during a prayer meeting at the Elmwood Avenue Free Baptist Church.

The artists in Providence honored Bannister’s grave with an 8-foot-high boulder bearing a bronze palette and a pipe, symbolizing his love for art. Arnold, who understood the challenges Bannister had overcome to achieve his artistic recognition, found this tribute somewhat inadequate.

(Conclusion)

John Nelson Arnold, a respected portraitist, believed that Bannister’s artistic legacy would endure. He observed that Bannister approached nature with a poet’s sensibility, capturing skies, rocks, trees, and distances on canvas with both vigor and poetic beauty. Arnold predicted that over time, Bannister would be recognized as one of the leading American painters.

In a time when American painting lagged behind European art, Arnold couldn’t foresee the eventual rise of the uniquely American Hudson River School, which celebrated the nation’s untamed wilderness and vast landscapes. Despite witnessing the Civil War and the end of slavery and seeing his Black friend gain national recognition, Arnold couldn’t predict that persistent racial prejudice would lead to Bannister’s omission from 19th-century American landscape painting histories.

Today, Bannister’s significance extends beyond his paintings. His life serves as a testament to the fact that America wasn’t always consumed by intense racism. His achievements highlight the contributions Black people have made in a democratic society, enriching the lives of all its citizens.

Source:

- Bearden, Romare and Henderson, Harry (1993). “A History of African-American Artists: From 1792 to the Present,” Pantheon

- Town of St. Andrews, New Brunswick, Canada, Heritage Arts & Culture: https://www.townofsaintandrews.ca/community/heritage-arts-culture/

- Lowell Institute: https://lowellinstitute.org/about/

- “A Look Back at John Brown,” Finkleman, Paul, Prologue Magazine, Spring 2011, Vol. 43, No. 1, National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2011/spring/brown.html

- “Biography: John Brown,” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/john-brown

- “WILLIAM WELLS BROWN (CA. 1814-1884),” Engledew, Devin, Mar. 08, 2007, Blackpast, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/brown-william-wells-1814-1884/

- Studio Building (Boston, Massachusetts): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Studio_Building_(Boston,_Massachusetts)

- The Barbizon School: https://www.theartstory.org/movement/barbizon-school/