“Shotguns,” 1987, John Thomas Biggers

John Thomas Biggers was born on April 24th, 1924, in Gastonia, North Carolina and was the baby of seven children of Paul and Cora Finger Biggers. His parents attended Lincoln Academy; a school supported by the American Missionary Society. According to the book, The American Missionary, Lincoln Academy was a secondary school for Black children with twelve teachers and over two hundred students that served as both a day school and a boarding school in King Mountain, North Carolina.

Paul, John’s father, was a hardworking man who wore several hats. Not only was Paul Biggers a school principal of a three-room school, but he was also a Baptist preacher, a farmer and repaired shoes, all to support his family. Little John Biggers may have also been hard working but was like his mother too, because as he would recount later, she had an artist’s eye and saw beauty in almost everything.

The eldest children were industrious and tended their own gardens. They even constructed their own toys and once, with the help of an older brother, John made a scale model of Gastonia, carving houses, laying out streets and using moss to represent lawns. He would later consider this project to be his first real creative exercise.

Paul Biggers, John’s father, entertained his children with captivating stories rooted in African folklore. These stories were reinforced when he, like his parents, began to attend Lincoln Academy. The principal when John Biggers attended, Henry McDowell, had spent many years in Angola as a missionary and knew many African folktales and proverbs and applied those proverbs to the problems facing the Black Gastonian community.

Biggers’ father taught his children to write, placing special emphasis on the beauty of well-designed capital letters and rhythmical writing. Additionally, Mrs. Blue, his second-grade teacher instructed her students to copy colored photos of birds that came in Arm & Hammer baking soda boxes. I kind of wish they still had that. I buy baking soda all the time.

Anyway, in 1936, Paul Biggers – the principle, farmer, father, husband and reverend – passed away. John Biggers was only 12 years old, and it became urgent for him to help his mother.

With seven children to support, Cora Finger Biggers, cooked for White families and later worked in an orphanage. And to lighten Cora’s load, John and his older brother Joe, earned their way at the Lincoln Academy boarding school. John would rise at 4:00 a.m. to fire boilers in the school’s 11 buildings. His supervisor, helped him to secure other jobs as well. He encouraged the boy to work his way through college.

Biggers entered Hampton Institute – now known as Hampton University – in 1941 as a work-study student. His plan was to study heating and plumbing. Which would be a natural course to take since he already had so much experience with firing boilers. But as it turned out, one evening drawing class with Victor Lowenfeld profoundly changed his life and goals.

This was where Biggers’ career path pivoted and he began his journey as an artist and teacher. We discussed Lowenfeld briefly in our episode on Carroll Harris Simms. However, Lowenfeld had a big effect on several Black artists. Not only Simms and Biggers but other greats like Charles White and Elizabeth Catlett. Both, who I plan to cover very soon.

Lowenfeld was a psychologist, an artist and a teacher. He studied psychology and the connection with art in Vienna, where he initially worked with the mentally ill, prisoners, and the blind, instructing them to draw, paint, and sculpt. His research concluded that art could be a path to establishing identity and overcoming feelings of inadequacy. Lowenfeld then applied these findings to child development, using art as a tool for children to discover and build their confidence. With the publication of his 1947 book, Creative and Mental Growth, which Biggers helped illustrate, Lowenfeld altered and advanced art education. After arriving to the United States in 1939 as a Jewish refugee, Lowenfeld was hired as a psychologist at Hampton Institute.

So, Lowenfeld took his work from Austria and proposed an art course to help build the confidence of Hampton students, but the administration and faculty were like, ‘Ah nah – these students aren’t interested in art. However, he won permission for a one night a week drawing class without academic credit. There were 800 students, around 750 showed up. The next year, Biggers majored in art.

Lowenfeld’s first course of action was to get students to shift their focus to African sculpture instead of simulating traditional eurocentric modern art. He emphasized the power of African art through religion and its role in societies in various African cultures. With this approach, he began altering students’ views of their own heritage. It helped them redefine beauty in art and bolster pride.

Biggers had said, “African art – in fact, African culture generally- remain devoid of significance in our lives. I felt cut off from my heritage, which I suspected was estimable and something to be embraced.”

Lowenfeld asked students to identify places on campus where they felt sculptures and murals should be and then had them create the works they wanted there. He also brought a young talented artist couple to Hampton – the painter Charles White and the sculptor Elizabeth Catlett, the two I mentioned earlier. If the students believed there were no real Black artists, by bringing these two artists, this was Lowenfeld’s mic drop.

At Hampton, Charles White created a mural, titled, “The Contribution of the Negro to American Democracy,” which backed up everything Lowenfeld was talking about.

Biggers recalled later, “We stood around him in awe, watching this master draftsman model our heroes and ancestors… John Henry, Leadbelly, Shango and Harriet the Moses.” Biggers said he became White’s, “Unknown apprentice,” and did everything he could to help out.

Biggers made a decision. He was going to be a muralist too. As a student, he created two. One titled, “The Country Preacher,” which showed a traditional preacher giving a sermon that depicted African scenes. The second, was titled, “The Dying Soldier,” that showed a soldier’s death on the battlefield, with his childhood memories floating in the sky. In these, Biggers tried to emulate the eloquence of White.

White, Biggers and Lowenfeld often discussed the Mexican concept of the mural as a tool to inform and remind the community of their history and reinforce pride. Because Lowenfeld helped Biggers recognized the value in the rich traditions in Africa, Biggers said, “I began to see art not primarily as an individual expression of talent.” He said, “but as a responsibility to reflect the spirit and style of negro people. It became an awesome responsibility to me, not a fun thing at all.” So Biggers, with this mission, ignored the New York art scene, galleries and museums that were always so important to so many.

Biggers’ social statement in his work, was an intense focus on the beauty, dignity and value of rural Black people as they navigated their lives and celebrated their planting, harvesting, and community.

He served in the Navy during World War II. Then, when Lowenfeld got a position as head of the art department at Pennsylvania State University, Biggers followed him there and was so moved by his philosophy and influence that he considered Lowenfeld to be the greatest art teacher of the 20th century.

Biggers earned both his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in one year at Penn State, and he also married, Hazel Hales, his Hampton sweetheart. During this time, he worked on two murals in the Burrows Education Building, one titled, “Harvest Song,” showing people celebrating the Earth’s fruitfulness, and, “Night of the Poor,” illustrating the harshness and emotional effect of poverty.

In 1949, in a Houston community center, Biggers’ painting titled, The Baptismal, was exhibited and this work caught the attention of a woman named, Susan McAshan. McAshan was the daughter of a cotton magnate. She became a highly influential Houston community leader whose wide range of passions emphasized human capability through an increase to access of information, education and beauty. She convinced the president of Texas Southern University, Dr. R. O’Hara Lanier to hire Biggers to establish its Studio Arts program. Dr. O’Hara who was a former Hampton president was actually already familiar with both Biggers and his wife, Hazel.

Biggers had seen what starting an art department looked like, yet starting one at TSU in the early 1950s, was still quite a struggle. Faculty and staff were conditioned for practicality and felt art was not a great subject for their students. Biggers’ colleague, Joseph L. Mack, another Lowenfeld student, had been through this same frustrating resistance, suffering for two years of academic hostility to the idea of art programs for Black students at Florida A & M. But even though they had brought Biggers to establish an arts program, Biggers was given a small room with one arm lecture chair and no easels, or sculpture stands. Later, Biggers said he initially wanted to commit an act of violence every time he opened the door.

Though this was higher learning, regular art texts weren’t very helpful because the TSU students, at the time, weren’t prepared very well in English. Instead, they relied on Lowenfeld’s text, as well as Alain Locke’s book, “Negro in Art” and Aline Saarinen’s book titled, “Search for Form.” Biggers knew the students needed to feel like artist, so he had them saw the arms and backs off their lecture chairs paint the walls gray and began designing and painting murals on the walls. He wanted to crack open the students and free them from worry from what seemed standard and encouraged them to look within themselves, their own feelings and their personal histories for their subjects. According to A History of African-American Artists, Biggers taught his students that creativity, didn’t rest in the classroom or in books, but reclaiming of the poetic sensibilities of their childhood- it’s spontaneity, enthusiasm and pleasures.

Oh. The administration and faculty were beside themselves when they found out that the student would be depicting African-Americans. They weren’t buying Biggers’ assertion that Black people were the great caretakers of the earth. They were not yet able to see the value of empowering their students with love and pride of their own history, their own people, their own blood.

He had something to prove. Biggers entered a juried show at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts. His Conte crayon drawing titled, “The Candle,” won the Purchase Prize. So the press that came later validated what Biggers was doing. It started changing the attitudes of faculty. However, Biggers couldn’t personally accept his prize though, due to segregation. To further solidify the validity of Biggers’ approach, his painting titled, “Young Mother,” won the Atlanta University exhibition Purchase Prize in 1950.

In 1951, great praise was given to Biggers and Joseph L. Mack for their special faculty-student exhibition by the Texas Senate. In 1952, they created two murals for the Eliza Johnson Home for Aged Negroes. “The Harvesters” depicting people picking cotton, chopping wood, fishing and baptizing. The second mural titled, “The Gleaners” was that of people gathered, cooking and quilting. A little later, when Biggers began a YMCA mural featuring Harriet Tubman holding a rifle while leading slaves to freedom, some women in the community got so upset! He was making Black women look bad! Biggers did stop – until people from the YWCA convinced the ladies that this was a good thing – a positive thing – not a disgrace.

Apparently, Biggers got a good amount of press with his work – like a mural he painted at

Carver High School in Naples, Texas, and also another mural at the International Longshoreman’s Association, local 872, in Houston.

In 1957, a UNESCO grant enabled him and his wife, Hazel, to spend 6 months in West Africa, visiting Ghana, Nigeria, and Togo. UNESCO stands for the United Nations Educational, Scientific, Cultural Organization – a specialized agency of the United Nations. Of the trip, Biggers said, “I had a magnificent sense of coming home, of belonging.”

Anthropologist, such as Melville Herzegovits, had spent a lifetime searching for Africanisms surviving in Black American life, but he did have much success. According to Biggers, Herzegovits just didn’t recognize them. There were ways of doing things that were subtle, such as ways of standing, sitting, walking, handling tools, planting seeds, and weaving. When Biggers saw Africans building, working in the fields, cutting and shaping handles for tools, making shoes, constructing their own chairs, Biggers was excited. He documented his observation with drawings.

He made his drawings into a book, titled Ananse: The Web of African Life. “Ananse the spider is a well-used character in West African folklore, who is cunning and outwits larger animals. A little like Brer Rabbit in Black American folklore.

Many of these drawings were approached with photorealism. Yet, some of them abandoned detail and focused primarily on the shapes of human forms and movement of activities like fishing, drumming and dancing. Biggers also saw the creation of temporary clay and wooden sculptures in the fields, when new crops were planted to encourage in abundant crop. After the harvest, these sculptures were left to decompose and new ones were created each season.

But the trip wasn’t all heartwarming and exciting. Biggers was bothered by how some Africans accepted ” the White man’s image of them indiscriminately,” He was also upset to see that the art school he was visiting didn’t contain a single African sculpture. It was the same cultural oppression he was experiencing at TSU and Biggers would go back home newly galvanized to address it.

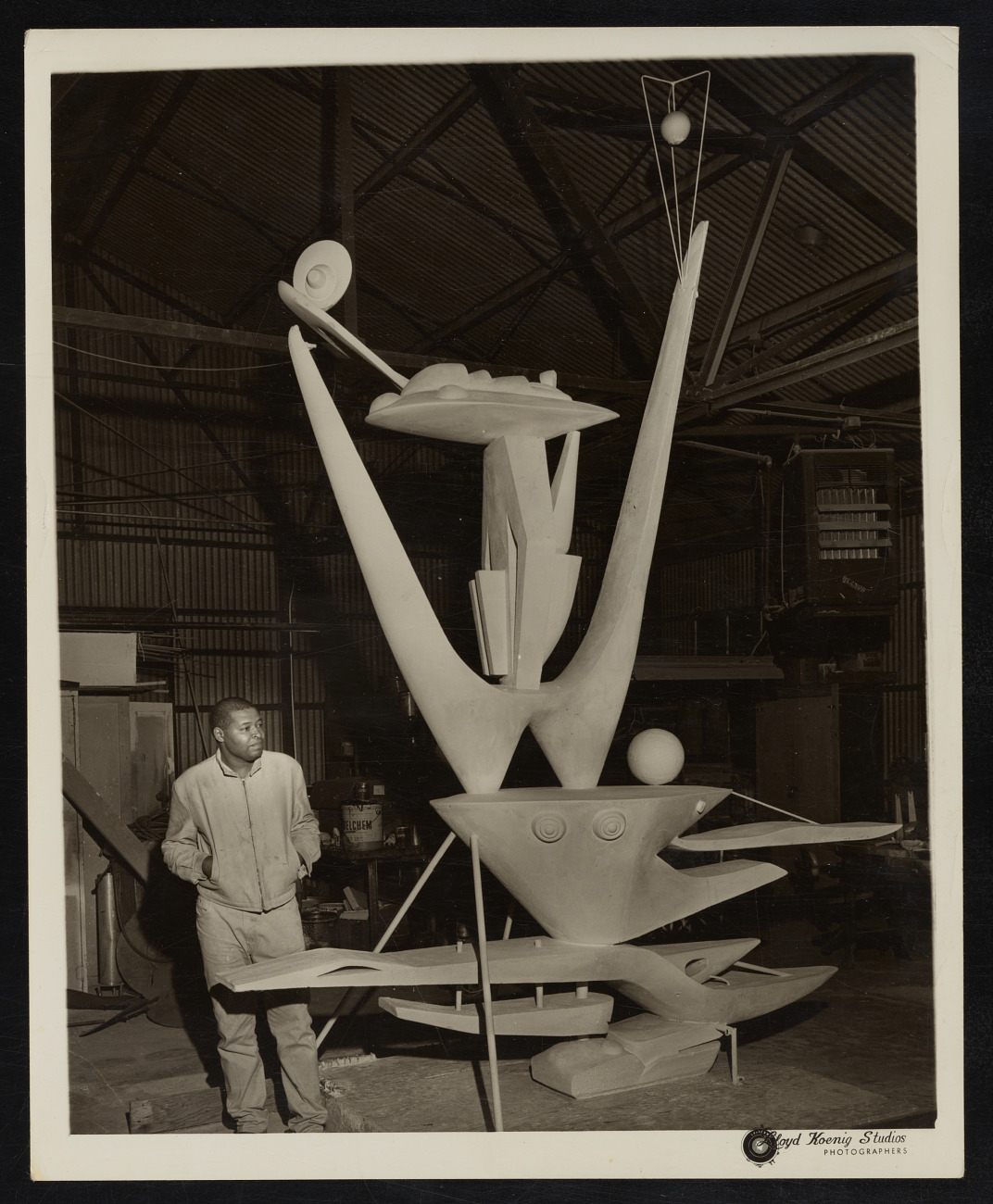

After returning to Houston from his West Africa trip, Biggers was asked to create a mural for TSU’s new science building. You might recall that Carroll H. Simms was asked to create a sculpture on that same building, which became his piece, titled, “Man the Universe,” and was inspired by Negro spirituals. Biggers chose to portray life as, “a single great system of activity due to the close relationship between organisms, ” specifically the biological interdependence of humans and nature. Some of the imagery was from his early biology studies, but some was from the concept of Mother Earth’s life force, supported through a central root system with Black women sewing and harvesting among flora and animals. Mimi Crossley of the Houston Post called this mural, “a National Treasure.”

In his mural titled, “Birth From the Sea,” Biggers stretches his imagination. This mural was created for the WL Johnson branch of the Houston Public library. It centers on a Black woman, draped in gauzy material as she stands in front of a fishing boat. Several female figures behind her are dressed in white. They gather on both sides of a fisherman on the right as he casts his net and a large fish creates waves in the background. Another woman, on the left, bends over her work. Biggers compared her to God bending over the clay while making the first man. I think this mural could have totally been a 70’s funk band album cover.

Speaking of the 70’s, in 1977, after suffering the cramped art space that once filled him with hostility, Biggers helped make plans for the new and improved TSU art center. It was a block-long, one story building with plenty of natural lighting, containing large studio areas for teaching drawing, design, painting, ceramics and sculpture.

Before he retired, each TSU art major was required to complete a mural in his or her senior year and wall space was reserved for them in various buildings. Low quality murals were eventually painted over and at one point there were reportedly 50 murals on campus. But after 1983, the mural program as well as Lowenfeld’s philosophy on self-identification, the crux of Biggers’ philosophy, was largely abandoned, replaced with more traditional academic Art School philosophies. When Biggers found out, he said he was disappointed, but not bitter.

The motifs that Biggers loved to explore centered around harvesting, planting, baptism and other rituals of rural Black communities. Also, he loved telling the story of the root system, the connectors of Black American life to the Motherland – whose children are the Earth’s caretakers.

His murals evoke beauty and allowed us to see ourselves and our ancestors in them. They allow us to be proud of our American lives without limiting the expectation of our capacity.

While he was in Africa, Biggers had said “when I heard the great drums call the people, when I saw the people respond with an enthusiasm unequal by any other call of man or God, I rejoiced. I knew that many of these intrinsic African values would never be lost in the dehumanizing scientific age – just as they were not lost during the dark centuries of slavery.”

Biggers received many life achievement awards including the Creativity Award from the Texas Arts Alliance and Texas Commission on the Arts awarded in 1983; and the Achievement Award from the Metropolitan Arts Foundation and the Texas Artist of the Year from the Art League of Houston, both awarded in 1988. He also received an honorary doctorate of Humane Letters from Hampton University in 1990.

Alvia J. Wardlaw curated a traveling exhibition in 1995, titled, “The Art of John Biggers: View from the Upper Room” at the Museum of Fine Art in Houston. This exhibition featured over 125 works, spanning his fifty-year career, including works he completed after his retirement. This show was later made into a book by the same name.

Thoughout the 1990’s, Biggers continued creating murals with his nephew, James Biggers, and Harvey Johnson. From 1997 to 1999, Biggers painted his final murals in Houston, “Salt Marsh” in 1998 and “Nubia: The Origins of Business and Commerce” in 1999.

On January 25, 2001, in Houston, Texas, John Biggers died in Houston, at the age of 76.

This episode was researched and produced by me, Kobina Wright. The theme music was created by Addae. To see images from this episode, go to our website at Thewholeartnebula.com.

Also, you can see a few animated episodes on my YouTube channel, “A Fat Slice of Cake.” If you’d like to support and learn more about me, go to Kobina-Wright.pixpa.com. Each purchase from the site goes towards helping this ship run a little smoother. And if you liked this episode, I’d be so happy if you left a five-star review.

Source Material:

- Encyclopedia.com – John T. Biggers: https://www.encyclopedia.com/african-american-focus/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/biggers-john-t

- A History of African-American Artists: From 1792 to the Present, Romare Bearden & Harry Henderson, 1993, Pantheon, pp. 447-453

- UNESCO: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:United_Nations_Educational,_Scientific_and_Cultural_Organization_(UNESCO)

- About Susan McAshan: https://cswgs.rice.edu/sites/g/files/bxs3966/files/2020-11/McAshan%20Bio.pdf